The Role of Calibration in Risk Analysis

HDR’s Calibration Training: Team Calibrator – Hubbard Decision Research

Managing risk requires making decisions under uncertainty, often before complete information is available. One of the most common objections we encounter when working with clients concerns the lack of data to inform quantitative model inputs. When data are easily accessible, leveraging them to generate empirical inputs is straightforward. Gaps still arise, however, or data collection becomes impractical, especially early in a project. Under such conditions, we rely on “calibrated estimates” from subject matter experts (SMEs).

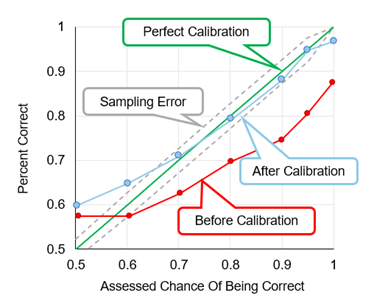

Every measurement instrument requires calibration, whether the instrument involves a precision manufacturing tool or human judgment used in model building. Calibration depends on consistent and unambiguous feedback. Prior to calibration, measurement error is often quite large. Humans tend to be systematically overconfident when making estimates, which introduces error and reduces model realism. Such overconfidence appears both in 90% confidence-interval range estimates and in probability estimates for binary events.

In training more than 3,000 individuals through consulting engagements and standalone programs, HDR has repeatedly observed this pattern of overconfidence. Calibration exercises demonstrably improve performance. Our methods, along with those developed by Philip Tetlock and Roger Cooke—whose pioneering work in this field is well worth reading—align stated confidence with empirical accuracy. Calibration in this context means that a claim of 90% confidence in a range estimate corresponds, across repeated estimates, to correctness approximately 90% of the time within a statistically allowable error range.

Figure 1 illustrates the typical pattern observed for calibration improvement over time. Despite systematic improvement, several confidence levels remain difficult for aggregated groups to calibrate perfectly. Slight overconfidence commonly appears when individuals state 50% confidence in a binary event. Such statements suggest complete uncertainty, yet outcomes across many trials indicate the presence of some informational advantage. Slight overconfidence also appears near the 100% confidence level, where allowable error approaches zero. To address these residual effects, estimates are aggregated across multiple experts and adjusted using each expert’s observed calibration performance. Aggregation reduces individual bias, and final calibration adjustments further fine-tune estimates, producing more reliable inputs for decision models.

Figure 1

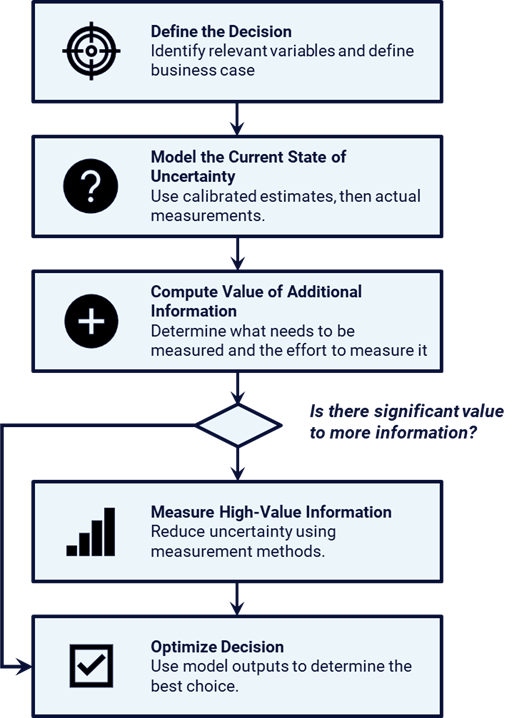

Improved estimation quality forms a critical component of the Applied Information Economics (AIE) framework. Organizations frequently face data gaps. A common reaction treats further analysis as impossible until those gaps are filled, prompting immediate, large-scale data collection. In contrast, AIE emphasizes decision definition and measurement of current knowledge before engaging in such efforts. As illustrated in Figure 2, the framework uses quantitative analysis to show where reducing uncertainty would meaningfully affect the decision.

Figure 2

AIE helps organizations avoid a common decision-making pitfall: Measurement Inversion. As termed by Doug Hubbard, the Measurement Inversion describes a repeatedly observed pattern in which organizations measure and collect data on factors that have little or no effect on decisions. Millions of dollars can be poured into these efforts. Doug Hubbard often remarks, “I honestly wonder how this doesn’t impact the GDP.” A reasonable response is that it probably does.

The first step of AIE, defining the decision, focuses on the choices under consideration, the outcomes that matter, and the uncertain variables that influence those outcomes. Risk analysis supports better decisions about which risk-reduction actions best serve the organization. Every organization faces many possible mitigations, controls, and initiatives, but determining which are justified requires quantitative analysis. Clear decision definition provides the foundation for prioritization.

Identification of variables that merit additional measurement follows from the next two AIE steps: modeling current knowledge and computing the value of additional information. Modeling current knowledge involves populating the model with “arm’s-reach” data and calibrated estimates. Calibration training ensures that uncertainty around each estimate is represented appropriately. Once the model is populated, analysis proceeds to calculation of the value of information (VOI), which indicates where additional measurement is worth the effort.

For example, consider a hypothetical capital project planning a major facility upgrade. Early cost and schedule data are incomplete, and the team considers delaying approval to collect detailed estimates across all work packages. AIE modeling using calibrated estimates shows that uncertainty in a small number of long-lead components drives most of the risk, while uncertainty in routine tasks has little impact on the decision. VOI analysis confirms that broad data collection would not change the outcome, whereas targeted measurement would.

VOI quantifies the economic impact of reducing uncertainty in specific model inputs. Ron Howard, a founder of decision analysis, introduced the concept in the 1960s, yet organizations still apply it infrequently. Many variables exhibit negligible information value, indicating that additional data collection or analysis would not affect decisions.

Before taking on a large data-collection effort, pause and ask whether that effort is actually justified. Avoid falling prey to Measurement Inversion. In many cases, decisions improve more from well-calibrated estimates than from indiscriminate data gathering. AIE provides a structured way to use calibrated judgment and value-of-information analysis to focus measurement on uncertainty that truly matters and to support better decisions.