Overview:

- A Trojan horse is anything that introduces risk to an organization through something that appears to be positive

- Measuring the wrong variables is a Trojan horse that infiltrates virtually every organization

- This phenomenon has a real cost that can be measured – and avoided

The Trojans stood at the walls, drunk from victory celebrations after they had previously watched the Greek fleets set sail away in retreat, having been defeated after nearly 10 years of constant warfare. They had little reason to suspect treachery when they saw the massive wooden horse just outside their gates, apparently a gift offering from the defeated Greeks. Because of their confidence – or overconfidence – they opened the gates and claimed the wooden horse as the spoils of war.

Later that night, after the Trojans lay in drunken stupor throughout the city, a force of Greek soldiers hidden in the horse emerged and opened the gates to the Greek army that had not retreated but had actually lay in wait just beyond sight of the city. Swords drawn and spears hefted, the Greek soldiers spread throughout the city and descended upon its people.

The end result is something any reader of The Illiad knows well: the inhabitants of Troy were slaughtered or sold into slavery, the city was razed to the ground, and the term “Trojan horse” became notorious for something deceitful and dangerous hiding as something innocuous and good.

Organizations are wising up to the fact that quantitative analysis is a vital part of making better decisions. Quantitative analysis can even seem like a gift, and used properly, it can be. However, the act of measuring and analyzing something can, in and of itself, introduce error – something Doug Hubbard calls the analysis placebo. Put another way, merely quantifying a concept and subjecting the data to an analytical process doesn’t mean you’re going to get better insights.

It’s not just what data you use, although that’s important. It’s not even how you make the measurements, which is also important. The easiest way to introduce error into your process is to measure the wrong things – and if you do, you’re bringing a Trojan horse into your decision-making.

Put another way, the problem is an insidious one: what you’re measuring may not matter at all, and may just be luring you into a false sense of security based on erroneous conclusions.

The One Phenomenon Every Quantitative Analyst Should Fear

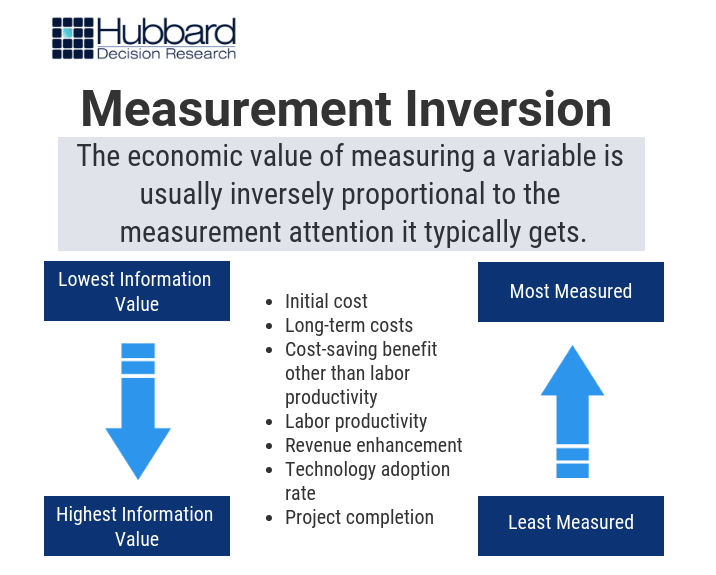

Over the past 20 years and throughout over 100 measurement projects, we’ve found a peculiar and pervasive phenomenon: that what organizations tend to measure the most often matters the least – and what they aren’t measuring tends to matter the most. This phenomenon is what we call measurement inversion, and it’s best demonstrated by the following image of a typical large software development project (Figure 1):

Figure 1: Measurement Inversion

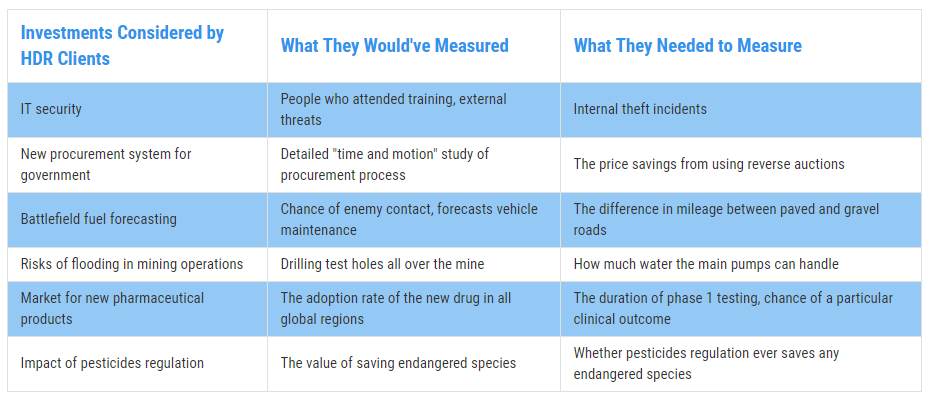

Some examples of measurement inversion we’ve discovered are shown below (Figure 2):

Figure 2: Real Examples of Measurement Inversion

There are many reasons for measurement inversion, ranging from the innate inconsistency and overconfidence in subjective human assessment to organizational inertia where we measure what we’ve always measured, or what “best practices” say we should measure. Regardless of the reason, every decision-maker should know one, vital reality: measurement inversion can be incredibly costly.

Calculating the Cost of Measurement Inversion for Your Company

The Trojan horse cost Troy everything. That probably won’t be the case for your organization, as far as one measurement goes. But there is a cost to introducing error into your analysis process, and that cost can be calculated like anything else.

We uncover the value of each piece of information with a process appropriately named Value of Information Analysis (VIA). VIA is based on the simple yet profound premise that each thing we decide to measure comes with a cost and an expected value, just like the decisions these measurements are intended to inform. Put another way, as Doug says in How to Measure Anything, “Knowing the value of the measurement affects how we might measure something or even whether we need to measure it at all.” VIA is designed to determine this value, with the theory that choosing higher-value measurements should lead to higher-value decisions.

Over time, Doug has uncovered some surprising revelations using this method:

- Most of the variables used in a typical model have an information value of zero

- The variables with the highest information value were usually never measured

- The most measured variables had low to no value.

The lower the information value of your variables, the less value you’ll generate from your model. But how does this translate into costs?

A model can calculate what we call your Overall Expected Opportunity Loss (EOL), or the average of each expected outcome that could happen as a result of your current decision, without measuring any further. We want to get the EOL as close to zero as possible. Each decision we make can either grow the EOL or shrink it. And each variable we measure can influence those decisions. Ergo, what we measure impacts our expected loss, for better or for worse.

If the variables you’re measuring have a low information value – or an information value of zero – you’ll waste resources measuring them and do little to nothing to reduce your EOL. The cost of error, then, is the difference between your EOL with these low-value variables and the EOL with more-valuable variables.

Case in point: Doug performed a VIA for an organization called CGIAR. You can read the full case study in How to Measure Anything, but the gist of the experience is this: by measuring the right variables, the model was able to reduce the EOL for a specific decision – in this case, a water management system – from $24 million to under $4 million. That’s a reduction of 85%.

Put another way, if they had measured the wrong variables, then they would’ve incurred a possible cost of $20 million, or 85% of the value of the decision.

The bottom line is simple. Measurement inversion comes with a real cost for your business, one that can be calculated. This raises important questions that every decision-maker needs to answer for every decision:

- Are we measuring the right things?

- How do we know if we are?

- What is the cost if we aren’t?

If you can answer these questions, and get on the right path toward better quantitative analysis, you can be more like the victorious Greeks – and less like the citizens of a city that no longer exists, all because what they thought was a gift was the terrible vehicle of their destruction.

Learn how to start measuring variables the right way – and create better outcomes – with our hybrid learning course, How To Measure Anything: Principles of Applied Information Economics.